The sunrise over the Atlantic came cloaked in rich, vibrant pinks. It relished its entrance, moody and least of all subtle. From the sun room window, I could see the huge boulders beginning to glitter with morning light. Just over those, the ocean. I could hear it through the windows, and let the caffeine from my first cup of coffee wash up in my bloodstream like the waves on the shoreline beyond. My friend, Holly, and I will walk that shoreline shortly. And then we will step into the icy water and attempt to not panic. Before the next low tide, when we can again actually touch feet to sand, we will commit Pink Lady Crimes.

Who am I kidding.

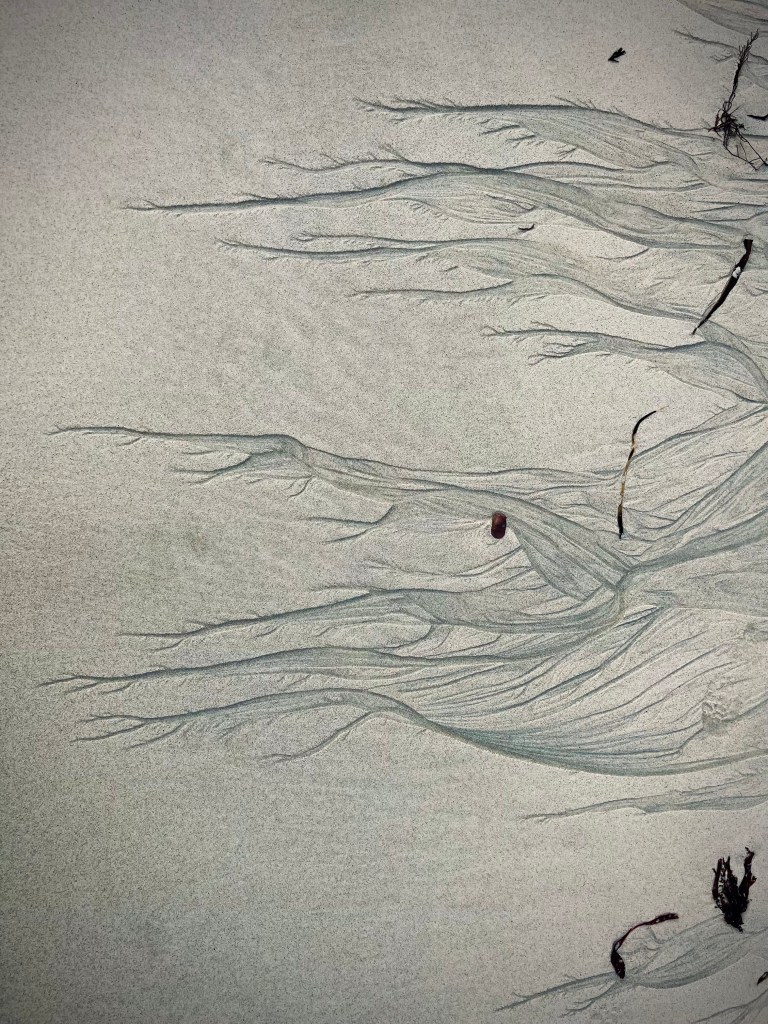

We are committing Pink Lady Crimes just by being here. We have chosen to take two nights, shut off our responsibilities, close ourselves into an airy 100 year old beach house rental on the New Hampshire coastline of Portsmouth, and write whatever comes to mind. We’ve packed food and notebooks and pens to fill our days. We are silent for minutes at a time, and as our comfort increases– the comfort we remember from being roommates back in our early 20s– the silence increases. Then it’s a couple of hours. Then a whole afternoon. By the time we walk the shore again in the evening, fully dressed, zipped up with coats and hats and scarves, we’ve written the day away. Then we take ourselves out to one of the nicest meals I can remember sitting down to, return to our nest, and share what we wrote over a sweet creme brulee port. In the morning, we watch a second sunrise. We get two this trip. Packed up by late morning, we take one more walk on the beach.

“Just over there,” I point again across the water, “Right there, is Scotland.” I feel like I can see it when I squint. I can see a version of me, one year ago, standing on the Western shore of the North Sea, shivering as I dip myself down into the cold ocean and think, Just over there, that’s New Hampshire.

It’s Scotland I remembered when I asked Holly to take this trip with me. Because Scotland, on the mystical Isle of Iona, is where I first learned the name for Pink Lady Crimes. From the Pink Lady herself.

The story Julia read aloud was sent to her by a friend. The basics are this– that a woman went to Iona, climbed the hill– sometimes exaggerated to a mountain– of Dun-I, and happened upon a pool of water fed by a spring. The woman experienced the inexplicable when encountering this pool, hearing the tinkling of shells and sees a vision of a bright pink orb, and believes she has stumbled upon the “well of eternal youth.” Years later, the woman becomes very sick and almost dies, and The Pink Lady– the glowing figure she saw on Dun-I– appears to the woman and tells her to return. She does. And the message she receives? Music Is Life. That the only way to touch eternity was to make music. You could beckon the Pink Lady, this eternal youth, by making sound or washing your face in the pool. The end. But what made the story extraordinary for myself and the four other women who had made their own pilgrimage to Iona to take a niche course in bookbinding, was the story’s complete lack of brevity or point. As Julia read on and on and on, we found ourselves as grown women with fits of giggles, like a joke that kept repeating itself until it became funny again and again.

We were strangers that very morning, finding one another based on the clothing we indicated by email we sent the night before what we would be wearing. We traveled from the shore of Oban across the water to Mull, took a bus across the expanse of the Isle of Mull, then took one last ferry ride to Iona. Maybe it was the delight of finding– with what odds?– like minded spirits so far from home, or maybe the candlelight, or of being well fed, or even our exhaustion, but we could not stop laughing until Julia finally finished reading. It wasn’t that we didn’t believe this woman had a special experience, nor were we mocking her. Maybe only that Magic seems impossibly simple and at once preposterous from the outside. Like watching someone else take a mushroom trip.

And so it was settled. When class was finished the next day, before supper, we would set out to find The Pink Lady ourselves. We closed the windows against the ocean breeze in the main cottage area and went to our separate rooms to rest up.

Class wrapped up right at four, and it was the promise of adventure that consoled us. We spent hours choosing driftwood, measuring, folding, stitching, drawing, and were each in our creative haven. Every moment was a treasure– the carefully curated seating for lunch by the Hebridean sheep, the tiny carrot cakes by Pauline, the bright light of the sun warming us as we worked. But now we were set loose to the island. We removed our house shoes and pulled on boots and jackets and began down the only paved road on Iona, looking for a white gate between a flower garden and a green roofed house that would take us to the foot of Dun-I. We pieced directions from the map, from our teacher– an islander now– as well as from the description given in the story from the night before. Though getting to the foot was easy enough, the route up seemed innavigable. We split up, Annette and Linda searching the low route, while Julia and I scaled a grassy knoll that ended in a vertical stone wall several feet in height. We met again at the muddy intersection where the path ended and the mound, now feeling much more like a mountain, began. We scanned the map again. Annette and Linda searched another path while I eyed the rocky trench that cut upward beyond us. Julia followed my eyes, turned to me and asked

“If you weren’t here with all these old ladies, would you go?”

“I’d go later,” I said, cheerful and unwilling to pressure my new 75 year old friend up a Scottish mountain. “I wouldn’t abandon ship.”

And without missing a beat, Julia said, “Then let’s go.”

Annette and Linda waved their goodbye and watched as we traversed the ravine, laughing and waving after each rock. It was boggy, uneven, and slippery. Still, Julia continued. I quit asking, “Are you sure?” and put myself to more useful work of instructing her feet, testing each step before her. Then, I lent her my hand. Soon, as the pass became more treacherous, I turned to her each time and asked, “Can you do this?” and she would respond, as if practiced, “Let’s try.” It became our mantra. By the time we reached the first landing, we were breathless but happy.

Then we looked up and I pointed to the next slope.

“Up there?” Julia asked.

“Yes,” I said.

“Okay,” she responded. And on we climbed.

With our friends now out of sight, the mound curling in intermittent alternating stretches of tall grass and rocky terrain, we found a rhythm. It was not that we were determined; we were compelled. It was a propulsion that became stronger and more inexplicable as we continued. We were tracking the Well of Eternal Youth. With that sort of promise, we could keep it slow, and our kinship grew. Julia had complete, unadulterated trust in me. And I had complete careful confidence in her willingness and enthusiasm to push on. We were together, becoming the brightest, truest versions of ourselves, and I had never felt so right and purely present.

Was it the Pink Lady? we asked ourselves, Was she behind this feeling? This connection? This onward pull?

At last we arrived at the top of Dun-I, a soft grassy knoll above bog, with large boulders edging up like fists pushing through the earth. It was not a peak, but a wide maze, no trail, no markers, just a view of the mound. We walked about the large cairn at the central hill and looked around. It was only word of mouth from here.

Look for the red roofs below and head toward the Lagandorain Croft, my teacher had told us. We saw no red roofs. I left Julia to catch her breath and tried one path. Then another. I ran back and forth, checking her in between, a canary for the mineshaft of misdirection and expended energy. Finally, a bend I thought I’d already taken, and I saw the red roofs. I walked further. At last. I ran back, laughing and screaming–

“Julia! Julia, we found it!” I came slipping up the hill. I found an easier path down, and we held hands and navigated our feet slowly, our legs now shaking from the trek up and across. We gasped as we stood, feet edged along a strange watery outcropping– like an infinity pool. We kneeled down to look at the various offerings– catholic icons, coins, a beautiful pink shell. The raised shore felt like an altar, sacred, beautiful, and as reflective as the water before us. I did not feel confidently able to reach in and not disturb the space, or to not fall in to the water below. We scanned the knoll, backing up and rounding the giant boulder that stood alongside the pool to the other side for better access. Julia’s legs were Jell-O, so we stood above the water a moment to take a picture, our long shadows of late day stretching beyond the spring– spirits looming within and above ourselves. She then watched as I moved through the bog, a creation of the draining spring, and kneeled to the earth. I smiled at her sunny silhouette, then dipped my hands in the cold water and pulled them to my face. The water was cold, cleansing, sharp in the March mountain air. And while the moment felt magic, it was incomplete. We had not come all this way together to leave the job half undone. I took a deep breath, dipped both hands back into the water, cupping them tightly, then stood balancing the sloshing liquid til I reached Julia. She held her hands out in a cup like mine and received the Well of Eternal Youth, tiny and powerful, and washed her face.

I have never known joy like that before.

We were triumphant.

We laughed and we cheered and we yelled and we said “I can’t believe we have done this!” When the uproar dulled a moment, we finally noticed.

The sun was setting.

We did not fret. We had been guided there, we would get back.

And then we took a wrong turn. Everything looked the same. I began to worry about Julia’s stamina, though she gave me no reason to do so, but the impulse to not backtrack set in. We scooted on our butts down a steep rock decline. We leaned over ledges.

“Give me your hand,” I’d say.

“Okay,” she’d say.

“Put your foot here,” I’d say.

“Okay,” she’d say.

“We took a wrong turn,” I’d say.

“Okay,” she’d say.

“Wait here,” I’d say.

“Okay.”

And on we went this way, her trust in me growing my confidence and humility at once. We would get down. Because we believed we would, and because we had to. And then, on a trek out and back alone to give her time to rest, I hit a barbed wire fence. Too tall to climb. Too taut to pull open. Too steep on the other side to climb down even if we cleared the fence.

This was when I lost hope.

What if I couldn’t do it? What if I couldn’t get her home safely before dark? What if I run back, scared, and have to leave her?

That, I realized, was an impossibility. Julia and I shared a spirit on this mountain, and we could not be separated. I turned, breathing deeply and considering the problem as one that simply hadn’t been formally asked for a solution. I called on the Pink Lady, on the North Sea, on the spirit of Julia who believed in me, and that’s when I saw it. We’d overshot by one hill. We’d have to climb back up, but only once more. I ran back.

“One more hill, Julia!” I called.

“Okay!” she said, her enthusiasm not wavering.

And it was okay. Slowly, slowly we ascended; then slowly, slowly we descended again. By the time we reached the spot we’d last seen our friends, our tiniest muscles ached from the gripping and climbing and intentional movement. At last, the mound leveled to field, and then field to gate, gate to road. We laughed and watched the last light of the sun move behind the ocean and worried for our friends’ worry back at our temporary home.

“Do you go hiking a lot with your 80 year old grandma or something?” Julia asked.

I laughed, “Just you, Julia,” I said, “Only you.”

We passed a monk on the road. He could not comprehend our joy through his dourness. Then we burst in the doors of home, victorious, our friends clapping and cheering and oohing over our big adventure as we retold it with big arm gestures and photos. We all thanked the Pink Lady as Linda recounted her worry, of searching for the nearest helicopter dispatch should our journey have taken a different road– the road I’d feared at that barbed wire fence.

We recounted the story again to our teacher when she returned for dinner, an extra celebratory affair. I ate ravenously next to Julia, a magician’s trick by Pauline of leek stew with spinach and fava beans, roasted cabbage steak, and local smoked mussels– as well as a mixed green salad, and au gratin. We relished an apple-pear crumble with coconut yogurt cream before the soreness began to set in. I wished Julia a good sleep as we parted for the night.

I puttered a bit before bed, boiling water and staring outside. Annette had set herself up at the long table after dinner, preparing for a late night experiment with shells and paper.

“It was very brave of you, to take a 75 year old woman up like that,” she said.

“Or very stupid,” I responded, the weight of the day suddenly falling on my hips, my chest.

“She trusted you, fully,” Annette responded, “You did well to bring her back safely.”

I was so proud of Julia then, of her courage, her vulnerability. And I was proud of myself, too. Annette’s words followed me back to my room as I peeled off my layers and pulled on soft, dry clothes, tucked a hot water bottle into the sheets and climbed into bed. There was no reason this should have ended the way it did. Because I am not brave. It has been so long since I last felt able enough to lead myself out of bed, let alone lead a stranger up an unknown mountain. We needed each other, Julia and I. But I needed her more than the other way around. I may have taken her out and back safely up a hill. But she led me back to myself. My strong and able self.

The morning sky forced me awake. I couldn’t stay in bed. I rose and opened my studio apartment door to fresh air, to let the sea in. I managed a meditation, but only a short one. I hated to close my eyes for one second of waking on Iona. Then, I changed into a swimsuit and pulled over the poncho towel my cold plunging teacher lent me for my stay, and walked toward the sea, unlatching and relatching gates behind me, calling a hello to the sheep as I slid my way down the sandy embankment to the water.

The day before, I gasped and swore and laughed as I got in, swam barely six strokes, and swam back again. The only cold I knew comparable was a river of snow melt in northern California. Today, the tide was up, but the water was calmer, kinder. I swam twenty strokes, twenty back. When I stood on shore, I wanted to go back in. My breath was still short, but like yesterday, I felt triumphant, jubilant. I was a junkie for living. I sang the whole way back.

I changed quickly and hurried to eat breakfast before class. My mug of coffee was ready and hot, thanks to Linda, and there at my place setting, a lovely string of shells rested neatly on my and Julia’s napkins. Julia and I looked around in surprise.

“It was late last night when I heard a tinkling of bells and shells and music drifting through the window,” Annette spoke, excitedly and with a plainspeak that lulled us right in, “And I swear I saw a shimmering of pink in the distance as I fell asleep. When I awoke, these necklaces lay where they are now.” She smiled then.

Though unconfirmed, we suspect Annette. Our first Pink Lady Crime. Julia and I wore them proudly the rest of the day. When our teacher arrived to begin class, she was appropriately amazed and delighted. Our creations that day were made with freedom, a sea wind, and a glimmering pink glow on all of our cheeks. It took every effort to tear ourselves away for lunch and a trip into town. This is the nature of Pink Lady Crimes. They spurn only more mystery, only more creativity, only more joy.

My swim the next morning was quieter. 26 strokes out, 26 back. I didn’t laugh or scream or jolt. I had come to find peace in the icy water. I was moved by the power of this entity I tried to befriend. I felt its embrace, and also its mood. When it rolled me back onto shore, I was filled with a deep gratitude. Thank you, I whispered, Thank you for letting me in, thank you for letting me go. Surely this water could have taken me as prisoner at its own whim and choosing. And it didn’t. I returned to myself and a plan formulated on my way up the sandy slope. Today, I would climb Dun-I, and I would bring the Pink Lady back down.

Pauline, our wizard of food and amiable companion throughout our stay, was game the moment I asked her. She finished breakfast for the rest of the ladies, and we took secretly to the hill. This time, I was not led by the Pink Lady. I was led by Pauline. And with her sure footing and knowledge of the path, we climbed a fence and took a steeper but faster hike up to the cairn, puffing at the top. From there, I led her to the spring, my memory easily finding the way once I was oriented to this marker. Pauline joined me in kneeling by the pool, where we both washed our faces, in what felt now like a rite of entrance, an inquiry. When it felt right, we filled a small pouch Pauline carried with water from the pool. Then we traipsed back down the other side. We did not miss a turn, but still scrambled a few rocks, and we were on the road and back to class before it began.

I tried to emulate Annette’s surety and lilt as I poured the water into a large silver bowl and presented it to the women at the table. Each sat with their nearly finished books in front of them, the driftwood covers chosen and drilled and preparing to be stitched in the day ahead.

“I thought I saw that pink glowing light at the top of the Dun-I again– Pauline saw it, too. So we followed it up. And the Pink Lady, she was there, and asked that we bring this back down with us.”

These women, these friends, each responded with sanctity and delight as I carried the bowl around. They dipped their fingers in and blessed their faces, and the cover of their books. It was not as smooth as I’d have liked, and I may not have pulled it off without suspicion, but as I sat down to begin class and complete my book, I felt the satisfaction of having committed my first Pink Lady Crime.

What fun! I can still hear Annette say, with her golden laugh repeating, What fun!

To define a Pink Lady Crime is to try and hold water in your hands. It can be done, but only as far as a nearby person is standing, waiting with clasped hands to receive it. It’s loose and floats into unexpected stories. Maybe its reduction is Random Acts of Creative Kindness. A handmade card to a friend. A shell necklace. Writing a song for someone. A very special cake for a not very special occasion. Wandering on a shore with a new friend on a faraway Scottish Isle because you heard a rumor that the best sea glass is there.

The how of it is even less clear. Unprompted, in partial secret, with the guide of an unexpected discovery, love, and perhaps a little craving for adventure. But always, the “why” remains unspoken. A shrug, a raise of the eyebrows, and a smirk will do.

The impact is most pertinent, as a Pink Lady Crime is rarely the completion of something, but rather the beginning. It’s the plant of a mystery or a new story, It’s the resurrection of a long lost imagination. This is the piece that, even as the one committing the crime, you get to keep even as you give it away.

Its categorization as a crime is that it is an absolute offense to the crush of reality. It looks at the ordinary and absolute and says– maybe not. Maybe instead, there is an extraordinary explanation. Maybe there is a solution we have not yet uncovered. We are asked to grind our bodies and our brains and our defenses against the rigid, defensive rocks of societal expectations and demands for more and harder and excess and criticism and analytics til we have gripped the ever-loving life from living. A Pink Lady Crime needles the definite and says, But what if it’s not. What if I don’t have to work smarter or harder, but I instead took a walk I don’t have time for with a friend and breathed in the bitter February snow? What if I believed that a strange pink glowing orb took me to the top of a mountain in Scotland? Or take it further– what if I believed that my neighbor had my best interest in mind? How would I respond to a world that is soft and lush and full of mystery compared to a world that is harsh and waiting to harm me? I would respond by trying to make the world softer for someone else. And then crime becomes rampant.

I drove home from my writing retreat last weekend just in time before the snow storm hit. We are socked in, now, with mounds taller than our truck that our neighbor keeps building up every time he plows. I was exhausted when I got home, and high as a damn kite. I had committed a Pink Lady Crime by asking my friend to retreat with me. We somehow chose to believe that we could do this, that we could just write. And we did. I left with several pages, and Holly left with some beautiful poetry and stunning sketches of the sea. What felt impossible– to take time, to tell ourselves stories, to sprinkle magic on the lot of 2 1/2 days– and to do it with another person, disbelief be damned: that is a Pink Lady Crime.

I greeted my Someone with a thick, unbridled joy. Then I walked upstairs, laid down on the bed in the loft, and fell deeply asleep on top of its warm quilt for well over an hour. Committing crimes is exhausting. When I awoke, I saw a glow from the window. Outside, the snow was swirling around, creating a mist, a whirlpool of blue and pink. I was witness to another world. I was a captive in the imagination of the earth itself. Another Pink Lady Crime from Mother Nature to me. The world is full of them once you slow down to look.