I am a woman of prayer now. I guess as I have always been.

We left our home in New Hampshire on my Someone’s birthday at the beginning of June, holding our breaths as our home of 8 years rattled down I-91 through Vermont, hoping this tour would prove better than the last. I say hoping and not praying because I didn’t know yet that I am a woman of prayer. Last tour we survived a busted transmission, two strains of bronchitis, food poisoning, our dog almost dying, among a myriad of small paper cuts from the universe. For all of that, we felt pretty good, even if a little nervous.

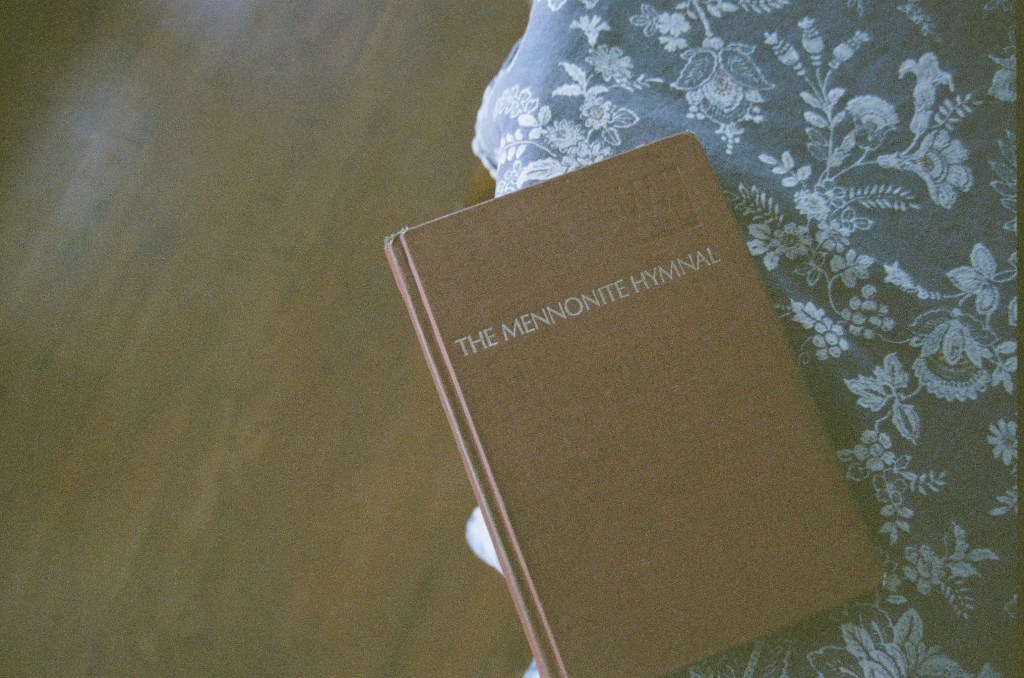

Our first stop landed us in a church in Upstate New York, a small town outside of the City that brims with quirk and quiet in the way that a celebrity pretends to be a nobody in public but secretly wishes someone else will notice anyway. We arrived at the rain location of our show that evening, decked out with a stained glass Jesus who looked to be about to inject a woman with a hypodermic needle and another Jesus who seemed to be sending the Apostle Peter adrift into the sea, head turned in a Bitch, Please fashion. I like these give-no-shits Jesus’, the kinds that just can’t with these chronic requests, anymore. I am far more comfortable with the relatable disgust of the world’s savior than with the eternal patience feigned by his followers, the passive aggressive “I’m praying for you” of which I’m frequently the recipient. Until later that night, when I met Don’t-Call-Me-Father Charles.

We followed our host to his home, instructed to bypass his driveway for the following parking lot, a large blacktop of an Episcopalian church. When we pulled in, a big pick-up truck was idling in front of the parsonage, a man inside shooting the breeze with another squat man hanging outside of the truck, smoking a cigarette. The smoking man waved our direction, but we ignored him as we turned ourselves around and parked, trying to look intentional enough to scare the intruders away. I told my Someone to cross the lawn to our host’s house while I got the animals settled. I’d just placed the hamster inside when the idling truck drove away and the smoking man called across the lot, walking toward me. I steeled myself until he got closer and said,

“Hi, I’m Charles. I’m the pastor here. I’m sick to death of it, but most people call me Father Charles,” at which point he broke into a thick Long Island accent, “‘Fathah Chahles! Fathah Chahles! Pray for me!’ Damn I’m sick of that shit. Don’t call me Father, just Charles.”

Much like with my Jesus of the hypodermic needle, I was immediately at ease. We talked music and travel in the dark parking lot, until my Someone approached, calling out, “Hello” in the gritted way he does when he feels unsure whether or not I’m okay. I assured him immediately, “Hey! Meet Don’t-Call-Me-Father Charles, he lives here.” Don’t-Call-Me-Father Charles said hello and lit another cigarette. He told us about his ex wife, his kid, his want to hit the road like we did. We told him about our house in New Hampshire, close to Dartmouth.

“Dartmouth!” he said, “That’s some luck if you ever get sick.”

“We know it,” I said, “we have a pal with cancer right now, and we’re awfully grateful for him to be so close.”

Don’t-Call-Me-Father Charles looked at me closely without pause, “What is his first name?”

“John,” I said.

“I will remember John this evening when I pray,” he said, then he took a puff while I took a breath, shot the shit a little more, then said goodnight. But I couldn’t get it out of my head– out of my heart, really. This was a prayer I believed in. He didn’t ask details, he didn’t even ask for a last name. His measure of reciprocation was in balance with the measure of which we knew one another, of which I shared, of which the situation warranted. His response wasn’t performative or grandiose. He didn’t ask that we stop the conversation– that we stop seeing each other in the moment– to offer supplication to an Unknown. He didn’t reach over and look at me meaningfully while he held my hand and said, “I will pray for you.” But he didn’t brush me off, either. This was an act of reactive compassion– not from years of being a pastor, but from years of listening. As if he can’t help but care. Whether or not there is a god above to receive Don’t-Call-Me-Father Charles’ prayer, the prayer was complete and heard because Don’t-Call-Me-Father Charles heard me, told me he heard me, and held lightly and carefully in his hand the deep pain and fear I was accidentally expressing by telling a relative stranger about my friend who he will never meet.

Prayer, I learned, is not about telling god that we need something. Prayer is telling each other that we see and hear them. Then later, in the silence of our bedrooms with hands folded and eyes closed, we are holding a little space and time amid the clatter of catastrophes so that we, in the act of being selfishly wrapped up in someone else’s problems, can see and hear ourselves, too.

The skies muddied with smoke as we drove west, crossing nervously over the Canadian border as a shortcut to Michigan. The wildfires in Alberta were seizing the air right out from under our lungs, and by the time we arrived in Hamilton, Ontario in the early afternoon, a permanent haze sat over our friends’ home. After the first hugs since pre-pandemic and a tour from their sprout of their new dinosaur bedsheets, we settled in the garden for black bean tacos and then coffee. We rolled through the afternoon without noting the time, then stretched our legs on a walk with the dogs before we had to head again for the border.

Piper, stunning and round, days from a labor that would bring her a second little sprout, held out a small paper bag. I could smell it before she gave it to me– homemade soap pressed with rose petals, a beeswax hand salve, and a tall bunch of white sage wrapped in string. They’d grown it themselves last year.

“To burn for a better tour this time,” she said. I was grateful. We needed it. At the last moment, she thought of one more thing. I took a handful of small oranges gifted to me and piled them into my backpack. Then I ran down the stairs to my waiting family in the truck. We were full in belly and in spirit, and we drove away quickly to try and shed the sting of missing our friends which was already radiating. We were almost to Michigan when I got Piper’s text.

We just found your dropped sage.

I sunk. It had fallen on their front steps. It must have been knocked out by the bunch of oranges. Maybe this tour was going to be another doozy, after all. I felt ungrateful, disproportionately upset to have not cared for it better. Then,

But it will be here when we see you next and we will burn some for your journey.

Of course. The smoke of the sage on my behalf may be better than the smoke I make myself. Without asking, Piper had heard my prayer, and offered it up. I imagined the small lilty stream of sage smoke twirling upward in her house, out her screens, and mixing with the haze of the Alberta wildfires that hung around us. A smoky chorus on my behalf. Maybe a small prayer like that couldn’t be detected by the less devout eye. But me, I knew it was there, or going to be there. I was heard and I was seen and I was loved.

Piper, hear my prayer. Just like that, I was less alone.

We landed in Michigan before nightfall, and I felt the weight of the absence I’d been avoiding. It is in this state that my friend lives– my friend who has been my friend as long as my Someone and I have known each other; my friend who carefully told me she prays for me in earnest; my friend who does not speak to me anymore on the basis of needing to choose Christ over me. I’ve resented her prayers in the past, wrapped in sympathy and in a hope that I might one day find true joy in the lifeless judgmental faith that drives her. In recent years, I’ve come to accept her prayers, and even cherish them. If for a moment I might raise to the top of her mind, it doesn’t matter where those thoughts escape to from there– whether to a loving god or a spiteful one, the part that counts is the tethers that bound her heart to mine in those prayers.

I sent out my own prayer, in a text, to my friend Annie. I cast my cares upon her then told her I would throw those cares into Lake Michigan when I get there. Annie is my circle of trees, my shade and my root system and my barrier. I pray to her often, even when we aren’t able to speak. It happened this night that she heard me immediately.

It may be one less tree, but this one is rooted so deep it’s not going anywhere.

Annie, hear my prayer.

I slept better that night.

In the morning, we found a trail next to our camper, leading miles from the parking lot. Six miles later, we returned, dogs panting and our skin a little darker, the first bloom of summer on our bodies. A piece of paper fluttered across the sidewalk. I picked it up. It was a grocery list, sensibly, in the grocery store lot.

Mac n cheese Marleigh

Almond milk

English Muffin

Fruit cups

Breakfast (Renee)

Marleigh nuggets

Breakfast Sausage

Ramen noodles

Leaf lettuce

It took me a couple of reads to understand that Marleigh was a person, not a brand. I imagined from the cursive that it was a Grandmother, preparing a visit from her granddaughter. I imagined her the night before, calling and asking her daughter-in-law what it was that Marleigh would eat– would she like something special? Does she eat vegetables? She jots down the ideas as they come, hangs up, and presses the list into her purse. Not until she is leaving the supermarket the next morning, bags rustling as she juggles the cart out from under the hatchback does that list slip from her hand and wave off to the far end of the parking lot, where a woman and her dogs and her Someone are walking.

This list, I thought, is a prayer. A prayer that, when acted upon, may just come true– that Marleigh would have a really nice time with her grandmother. That she would get enough to eat. That she would be happy here. That she would feel loved. I tucked the list into my journal and prayed the same. I hope Marleigh has a most wonderful time.

“You’re putting a curse on her, you know,” my Someone said to me. We were in Minneapolis. The smoke had dissipated, but the heat remained. It was a thick 90 degrees in the afternoons, and we were walking the neighborhood hoping for sprinklers with our dogs.

“What do you mean?” I asked, but already knowing.

“I feel like when you write a song for songwriters, it curses them, it makes them unable to write again.”

“But she already quit writing,” I said.

“True, but it’s like you’re sealing the deal or something.”

I thought about it. We’d just written a song for my friend, the one who might still pray for me but doesn’t speak to me anymore.

“But your ex girlfriend wrote songs about you and you still write,” I said.

“Yes,” he said, “but I sang through it. I kept writing, which breaks the spell.”

I like witch stuff. Very much. It’s why I like Christianity sometimes– the weird spells and rituals and vengeances; the miracles and the incantations; the pretending of drinking the blood of the dead. But this felt distinctly different.

I thought of my friend Tom. Years ago, as his wife and my friend Ann tells it, they were on an RV trip around the country. Everything had gone wrong, as things on RV trips are wont to. While I couldn’t recall the details of the mishaps, the story culminates at a campground late one evening when they finally found a place to stay, and one more hiccup occurs. Tom, a very tall and imposing figure, is furious. He drops the tools he was holding, stands straight, looks up with his hands open and shaking and yells at the sky–

“BRING IT OOOOON!”

As Ann tells it, the sky ripped open and it began pouring rain on his head.

An answer to prayer.

“No,” I said to my Someone, “I am not cursing her. I am daring her.”

Because, as I understood in that moment, a dare is also a prayer. A dare is a call for whatever may come to come as it may, and to bring with it the fury and the force, however unpleasant. Because sometimes, when everything is wrong, a sudden burst of thunderstorm on one’s head would at least clear up the confusion of the pregnant silence that bullies between a man and a god; or presses between two friends.

I can’t curse anyone– especially not someone who is already creating their own hell. They’re already cursed by their own hand. Instead, I pray by writing a song. I make a dare, for something to happen. The importance of a prayer is not that it is answered, but that the sound or the smoke or the water or the tree limbs of it rise up and are heard by someone– anyone. Even if that person is yourself.

Maybe my friend is still praying for me. Maybe it is frustrating for her, because she prays and prays to a god in the sky and she has seen no rain and has smelled no smoke and has had no one put her favorite kind of chicken nuggets on their grocery list in return. But I’m hopeful one day to do her the favor that I’ve been given again and again. I want to give her the gift of someone else looking at her and saying, “I heard that.”

Because that is simply the power of prayer.

Words have power…be it a prayer or a curse or a song. “In the beginning was the word…and the word was with God and the word was God”. Not that I’m a biblical scholar or a “good” christian but some words just stick with you and resonate…and have power..