“Love Trump, too?” Chris asked me backstage in the green room. “Trump, too?” he persisted before I had a chance to answer.

“Well, it would appear so,” I responded slowly. It seems I’d pigeonholed myself here. My Someone and I have been performing a song for the last couple of months in front of a myriad of people titled “Love Them, Too,” and the concept is as direct as the title. Mostly, it has highlighted our failings in the department of Loving Thy Neighbor. It has also created a small confession booth following our shows, of audience members approaching us and delivering their list of who in their life is impossible to love. Not with excuse– just as a fact. But the question Chris pushed back to me wasn’t something I hadn’t asked myself. It was a question I didn’t expect from someone else. And I was unprepared to give a definitive answer. What does it mean to love someone? What is my definition of love? What is his?

So, I got quiet, and Chris did, too. And we let that be an answer enough as he picked up his guitar and headed to the stage for his set.

We are one month since the election, and an entire season has passed. I have a whole journal full of my thoughts on the matter that don’t all that much matter. It is not that I am becoming despondent. It is that I am becoming water. It will come as little to no surprise that the results were not what I’d voted for, not what I’d hoped. The morning after Election Day, I did not try to fight reality like the first time. Instead, I asked my Someone for a cup of coffee, of which he promptly made and brought back to bed. And we sat and we watched the leaves dying outside of our bedroom window and we waited. We waited for the news to sink in. We waited for our feelings to settle. We waited for an answer of the next right thing. We waited for the sign that it was time to get out of bed.

And that is when I knew I would become water.

The first time around, I suffered. I checked my newsfeed chronically, I worried aloud with my friends, I posted snarky things on the internet, I called people names.

“I will not suffer this time,” I told my Someone. “We will not suffer this time.”

“Okay,” he agreed.

“Nothing we did worked before, and we can’t do it again. We will get hurt– things will hurt us– but we do not have to suffer.”

“Okay.”

“And if it doesn’t work?” I asked.

“If it doesn’t work, we can go back to staring at our phones and being irrationally angry with everyone,” he said.

My phone dinged. It was Alice. She worried about getting the medication she’d need for the next few years to maintain her health, and to continue her life as a woman.

Then it was fellow musician friends– “Are you okay?”

I closed my eyes. I took a deep breath.

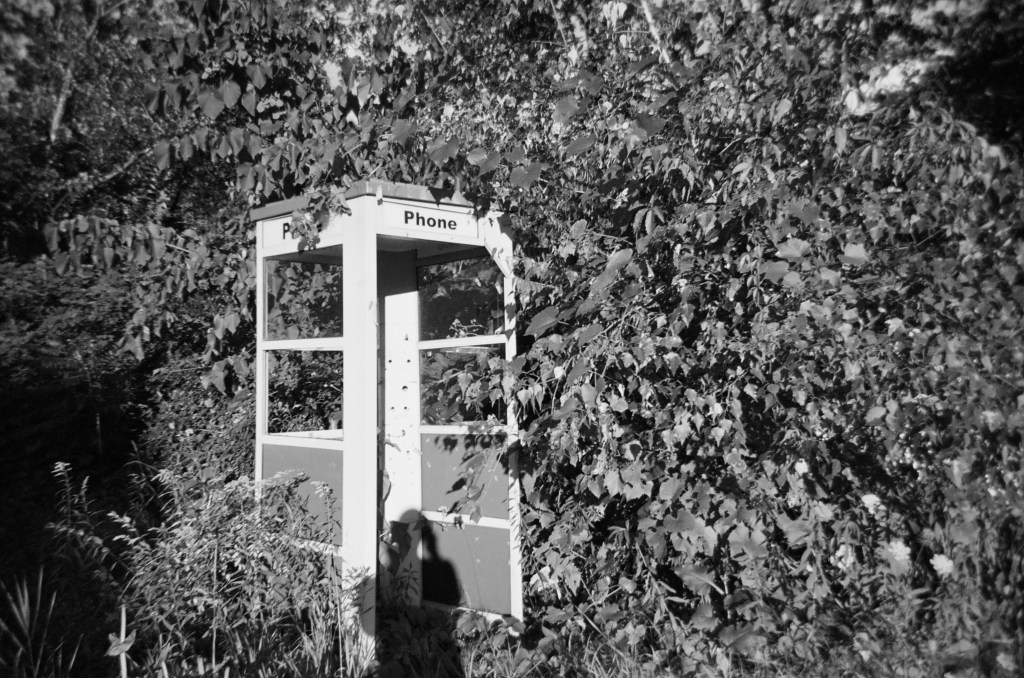

“Instead, I will become water. I will travel quietly and naturally to the lowest places. I will go to the darkest depths and I will wait there. And as I wait, it will erode; and when it erodes, and new path will form and we will all find a new way out.”

“We will become water,” he repeated.

We would become water, and we would begin The Great Experiment: to love our neighbors.

It was time to get out of bed.

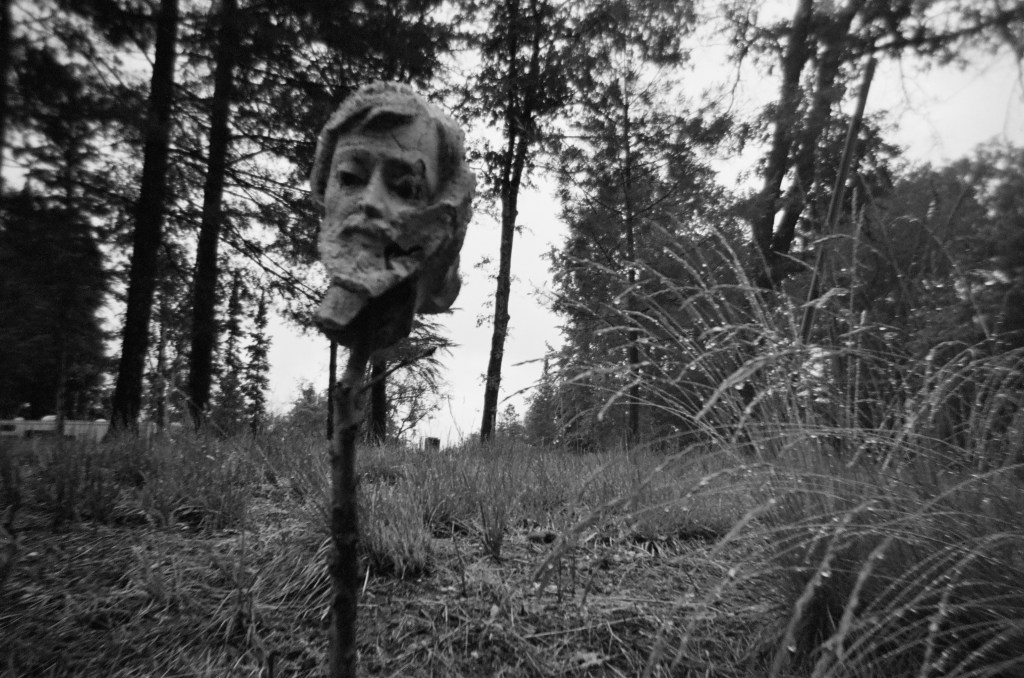

This is what I know to be true: that to call someone my enemy is to take away a small part of their humanity. And when I take a small part of their humanity, I care less about what happens to them. When I care less about what happens to them– when my ill-wishes become personally justified– I become a little less human, too.

So why do I do it? Why do I call someone names, or doom scroll for sarcastic memes, or preoccupy my mind with all the reasons that the “other side” is wrong? Or even preoccupy myself with their being “the other side?” Because it makes me right. The second I step from the ledge of fighting for someone to fighting against someone else, I can feel good about myself. Calling someone a Nazi makes me not a Nazi– which, in recent history, should be a sign of virtue. Calling someone an asshole when they cut me off in traffic means that I am a good driver. It feeds my ego. It makes me self righteous. I am justified because I am right. This, too, makes me not only the judge, but also the bringer of justice. I lay on my horn (he deserved it). I call someone a Big Orange Monster (well, it’s true). And how do I feel afterward?

A little empty. But for a second, I was right. And that felt good. So I do it again. Repeat repeat repeat until my ego is thoroughly protected in a bubble of righteous indignation that can neither hear nor see the small destructive path I am creating behind me in the name of justice. Which requires more evidence for the narrative of my rightness. Now, everything I see becomes a dichotomy of are-you-with-me-or-are-you-an-ignorant-traitor.

Don’t get me wrong– anger is good. Anger can bring clarity, and clarity can bring action. Note– action. Not reaction. That I become water and swell in a storm of anger may clear the space I need to see where I will flow next. Eventually, the storm must end. And then, I must reckon with settling again to the lowest places and waiting. Gently eroding, and waiting.

The day after Election Day, we put our feet on our floor to begin The Great Experiment. Fortunately, our friends Rowe & Laurie were coming over for coffee on the porch to help us decide what it meant. The weather was improbably perfect– overcast, gloomy, and a little warm. We talked about becoming water. We talked about not judging our circumstances by this particular moment in time. We practiced saying, “Maybe so.”

“Democracy is crumbling.”

“Maybe so.”

“It’ll work out.”

“Maybe so.”

“I am afraid for my friends.”

“Me, too.”

It was not indifference. It was not denying reality. It was simply not suffering. We told them about The Great Experiment– that we would love our neighbors.

“There is a way we could do it,” Laurie said, ever putting practice to parable, “We can start by drawing a small circle around ourselves and asking– ‘Is everything okay in here?’ and if the answer is ‘yes,’ then we make a bigger circle and ask again. When we get to a circle where someone is not okay, we stop and help and start drawing circles again. It’s what we could do.”

I could imagine it perfectly. I looked around the table. Laurie had lost her mother, Rosy, just a couple days before. Rosy was a cherished part of their home for a couple of years, and a cherished part of Laurie’s entire life. I drew a circle around us and asked myself, “Is everyone okay in here?” I noted the deep grief behind Laurie’s tired face and turned to my Someone, “I think we need another round of lattes for the table.” And so we stayed a little longer to visit until everyone was ready to stand up again.

The remainder of the day I drew circles around us. When a low spot formed in that circle, like water, I flowed that way. I tidied. I walked my dogs. Then, I drew a circle around my property. The gardens needed putting to bed. My Someone and I flowed to them and trimmed the raspberry bushes and the Asiatic Lilies, cut back the Aster, mulched the leaves and placed them on the beds, pushed ginseng seeds down into soil and firmly covered them again. As we pushed down our last seed, the sky opened up and it poured. I watched from the porch as the water fell and traveled to where the seeds were planted, and dribbled low to prepare them for their future growth.

I didn’t tell the water what to do. I didn’t force it. Instead, I repotted my houseplants and let the rain from the eves of the porch water them in their bigger pots. Then I carried them inside, confident the rain would do its job just fine without me watching. I drew another circle and found that everything and everyone in my circle was okay. I drew a bigger circle. Annie was afraid. I flowed to her. Our touring friends were scheduled to play a show in a place that was morally and politically opposed to them– I sat down and breathed deeply and flowed to them over text.

I found that my friends were drawing circles, too, and that I was inside of them. I assured them my oxygen mask was on, and asked if theirs was, too. Janelle wrote– “From the top down, it seems we are in a lot of trouble. So we need to be an encouragement from the ground up.”

Janelle was also becoming water. I was happy to be sitting alongside her, waiting and eroding and making a new path. It’s no small thing to draw a circle around only yourself and to make sure you are okay. Inner peace isn’t just necessary. It becomes contagious.

“Love Trump, too? Trump, too?”

The urgency of Chris’ voice still socks me in the forehead. I flinch when I hear it replayed. I can say this– I am trying. My circle, maybe, has not yet been drawn that wide. But I know this– when I saw the news come in earlier this year that he had been shot in the Pennsylvania town next to mine growing up, a deep, irrepressible phrase bubbled from my mouth–

“Not like this. Not like this. We don’t want this.”

Violence will only beget violence. Hatred with hatred. That was the moment, for the first time, that I realized I was capable of a love much bigger than myself. And that it was much harder, much more work, than being right. So from the bottom up, I am waiting. I am widening my circle to include my mother. Here, I have had to stop and investigate. Everything here does not feel okay. And so I recognize that– though she herself may identify as her political affiliation, it is not who she really is. I remind myself that she is also a person who texts my niece every day before school with three emojis on our family thread that describe what her day will be like. Loving her is no small task, because contrary to popular belief, love is not blind. Love is eyes wide open with a smidge of mirror tucked in. Love is water– it waits, it erodes what is unnecessary slowly, and all the while requiring us to look back at ourselves as we do. And then we draw another circle.